I was absolutely buzzing on Sunday morning as our group met early for Breakfast at the Sheraton hotel. It felt good to see Andy again. The curse of having friends around the World is that you don’t get to see them as often as you would like and the truth is I should make more effort than I do to talk to my friends more often. It was largely this feeling of being on an amazing adventure with such good people that had me grinning from ear to ear on the way to breakfast at 0630. That and I had also arranged an in person wake up call for Robin at 0545 to ensure he wouldn’t be late for breakfast. He was still late of course, but still worth it.

The drive from Nairobi to Tsavo was largely uneventful despite us taking a slightly circuitous route to avoid traffic delays in Nairobi and on the main Mombasa road. It was good to be back in rural Kenya after a few days in Nairobi and I was happy just to let the passing towns and villages wash over me with their familiar billboard adverts for Mpesa, Safaricom and Crown Paint (‘If you love it. Crown it!’) flashing past raising a touch of nostalgia. The heat built fast as we dropped down from the rift valley heading towards the lower savannah of Tsavo and the cash crops of pineapple, coffee, tea took over the fields at the sides of the road. A brief stop at an army checkpoint slows us slightly but eventually we turn off the metaled roads, through the park gate into Tsavo and onto the red dirt roads I remembered.

“Nothing but breathing the air of Africa, and actually walking through it, can communicate the indescribable sensations”.

William Burchell

I was excited about finally getting to visit the Ithumba Reintegration Unit: the next stage on from the Sheldrick Orphanage in reintegrating orphaned elephants back into the wild and where the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust has created a masterpiece of conservation hospitality in the vastness of Tsavo East National Park. Since my first visit to the Nairobi orphanage in 2009, whilst at the Safari 7s with Shogun, I have always wanted to see the second part of an orphan’s journey back to being part of a wild elephant herd. These wins for conservation and for protecting elephants are so important to ensure the survival of the species. Poaching has dramatically reduced in Kenya but the effects of Human Wildlife Conflict are still all too real and so the work done by the Sheldrick family and their teams of dedicated staff are just as important as ever.

We arrive at Ithumba Camp and it blows us away. The beautiful simplicity belying the luxury it conceals. There are only four tents dotted around the communal lodge and pool area and linked by wooden treetop walkways. It is paradise and we begin to understand what we have in store on this incredible safari.

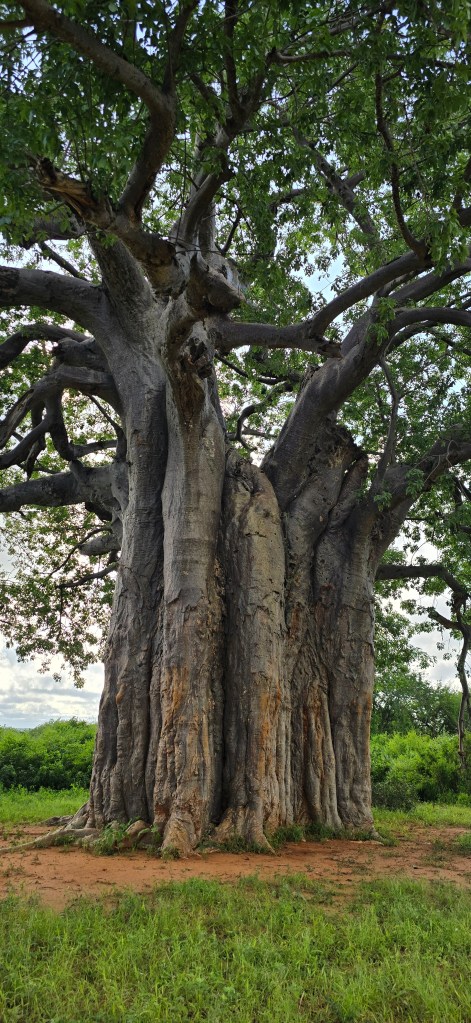

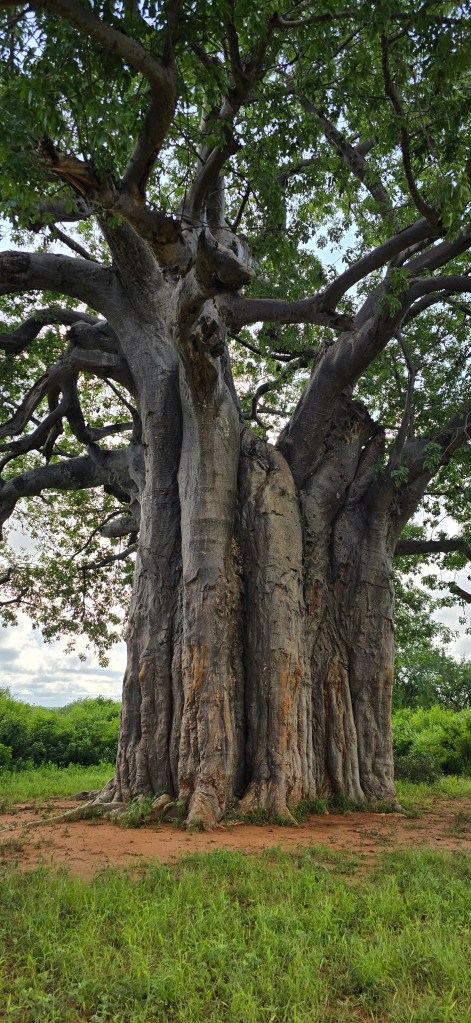

Ancient baobabs stand sentinel across the landscape, their enormous trunks resembling ancient sculptures against the ever-changing sky. From our elevated position in Ithumba Camp, the vista stretches endlessly – a tapestry of acacia, commiphora, lush greenery and golden savannah reaching toward distant purple hills. Each sunrise brings a new palette of oranges and pinks, while sunsets transform the landscape into a canvas of deep reds and golds before Venus, the evening star, heralds a night sky free of light pollution above our heads.

The night holds its own magic. Hyenas whoop in the darkness, their calls echoing faintly around Ithumba Hill, Rock Hyrax screech and wail, while for those still awake the elusive yet distinctive saw-like rasp of a leopard always sends shivers down spines. Our nightly walks from the lodge back to our tents become adventures in themselves, torch light revealing scorpions glowing like alien creatures on the walkways back to our tents. Katie’s previously undisclosed arachnophobia provides endless entertainment (and occasional chaos) as she encounters various eight-legged residents – though everyone agrees the scorpions are considerably more concerning than their spider cousins.

Days develop their own rhythm. Mornings begin with coffee and biscuits in the main lodge, watching the world wake up and come alive once again. Troops of monkeys play in the scattered trees and sneak through our accommodation while iridescent starlings swoop between branches. Delicate Dik-Diks tiptoe through the undergrowth becoming an almost ever present to our World, freezing like statues at any movement, while stately Kudu browse cautiously in the distance. Families of mongoose provide endless entertainment, scampering between rocks with their characteristic curiosity.

The pool becomes our afternoon sanctuary from the Tsavo heat, with Katie and Sophie turning bean bags into boats and then racing them around in what is sure to become an Olympic-level sport. Their shrieks of laughter compete with the constant commentary of the rock Hyrax, whose calls echo across the kopje with surprising volume for such relatively small creatures. The lunches are obscene especially when accompanied by endless wine and beer: every meal somehow being better than the last.

Chef James Dennis (whose son Oscar, I discover, I know from his Kenya 7s rugby days and who is now a successful para-athlete) transforms each meal into a culinary journey. His prawn curry becomes legendary among our group, while the tiramisu draws declarations of being “the best ever tasted in Kenya.” Each meal feels like a celebration, made more special by the spectacular dining room views across the park.

The food was incredible and I cannot recommend James and his team highly enough! If you don’t trust me just ask the cheeky Genet and its family who made a habit of breaking in to steal biscuits, cakes and the exceptional banana bread!

TRAVEL TIP – No matter how good the food always carry toilet paper, Imodium instants and electrolyte powder. I can also tell you that if you think you have used the worst toilet in the World: you haven’t. I can also tell you squatting over a hole in the floor in the pitch black doing an impersonation of an upside down chocolate fountain trying not to get any on you is a bizarrely welcome lesson in humility and a reminder that the World is just one bad day and a power cut away from the stone age.

Our trip with the orphan herd to the water hole was a real highlight. Young bulls practise their sparring while matriarchs keep watchful eyes on playful calves. After their bath the elephants roll in the piles of red Tsavo earth to coat themselves as protection against the sun. The afternoon light catches the red Tsavo dust coating their hides, creating an otherworldly glow around these magnificent creatures. Watching them you forget, for a moment, that these are all still young elephant and that they will get much bigger. To be this close to them, to interact with them in this way, is a huge privilege that should not be taken lightly. The keepers’ control is remarkable. A trust, built over years of time spent with the elephants as orphans that, as we witness time and again, remains even when they return to visit the integration unit as wild elephants.

The massive Tsavo bull elephant approaches deliberately down the ochre road, his tusks gleaming in the late afternoon light. We’re silent, motionless, as we watch his approach from the vehicle the only sound the whirring of my camera shutter as I capture his morning stroll. I’ve not often seen a bigger bull elephant; maybe in Lewa in the North of Kenya or in Botswana in southern Africa but in any case this one is huge. He is something to behold, majestic and noble and ancient. A throw back to when great beasts thronged these lands, to before humans polluted them with progress and civilisation. His ears are tattered from living among the Tsavo bush notorious for its thorns and barbs but the rest of him is in great condition.

My companions are surprised at how quiet he is; a five ton ninja gently making his way towards us so silently that we wouldn’t have heard him if he had passed us in the bush rather than walking down the road. He gets to within about thirty meters of us and finally notices us again, issuing us a little challenge just to remind us, as if we needed it, that he was there. He came forward another ten meters or so before quietly yielding the road to us and disappearing into the bush leaving us momentarily speechless at what we had seen before we all finally remember to breath out.

As the sun sets on our final evening, painting the sky in impossible colors, we reflect on the privilege of experiencing this place. It isn’t just another one of the many safari camps in Kenya – it’s a window into one of Africa’s most successful conservation stories. The story that started with David and Daphne Sheldrick and that became their family legacy is a triumphant fanfare to compassionate conservation. For us lucky few sat in the beautiful camp on the side of Ithumba Hill the morning chorus of birds, the midnight calls of predators, the constant comedy of monkeys, Genet and mongoose, and the majestic presence of elephants combine to create something truly magical that we will never forget. We sat and drank and watched the sky turn black as ink and it was all just as it should be. In Africa, sometimes things are exactly right. This was one of those times.

Those conservation success stories continue to astound us as on our final morning visit to the integration center, before heading to the airstrip, a wild elephant herd arrives with former orphans integrated into their ranks. Watching these ex-orphans moving confidently with their wild family members demonstrates the Trust’s remarkable achievement. Incredibly one of the former orphans has brought her own calf with her to meet the Sheldrick wardens: to introduce it to its extended family. I’m not going to lie. I walked away because someone close by was cutting up bags of onions.

Learning that Kauro, the elephant Buffy and I adopted in 2014, has fully transitioned to life with a wild herd fills us with particular pride. Each success story represents years of dedication from the Trust’s teams and ensures the ongoing survival of a keystone species. We were privileged to witness the full circle of rescue, rehabilitation, release and return. This corner of Kenya holds such a special place in conservation history. It’s where wilderness luxury meets purpose, where every stay helps write the next chapter in the story of Tsavo’s elephants and ensures that they will still be there long after we are gone. It also emphasises the power and value that safari tourism can bring and dismisses yet again the fallacy that hunting has any place in modern conservation.